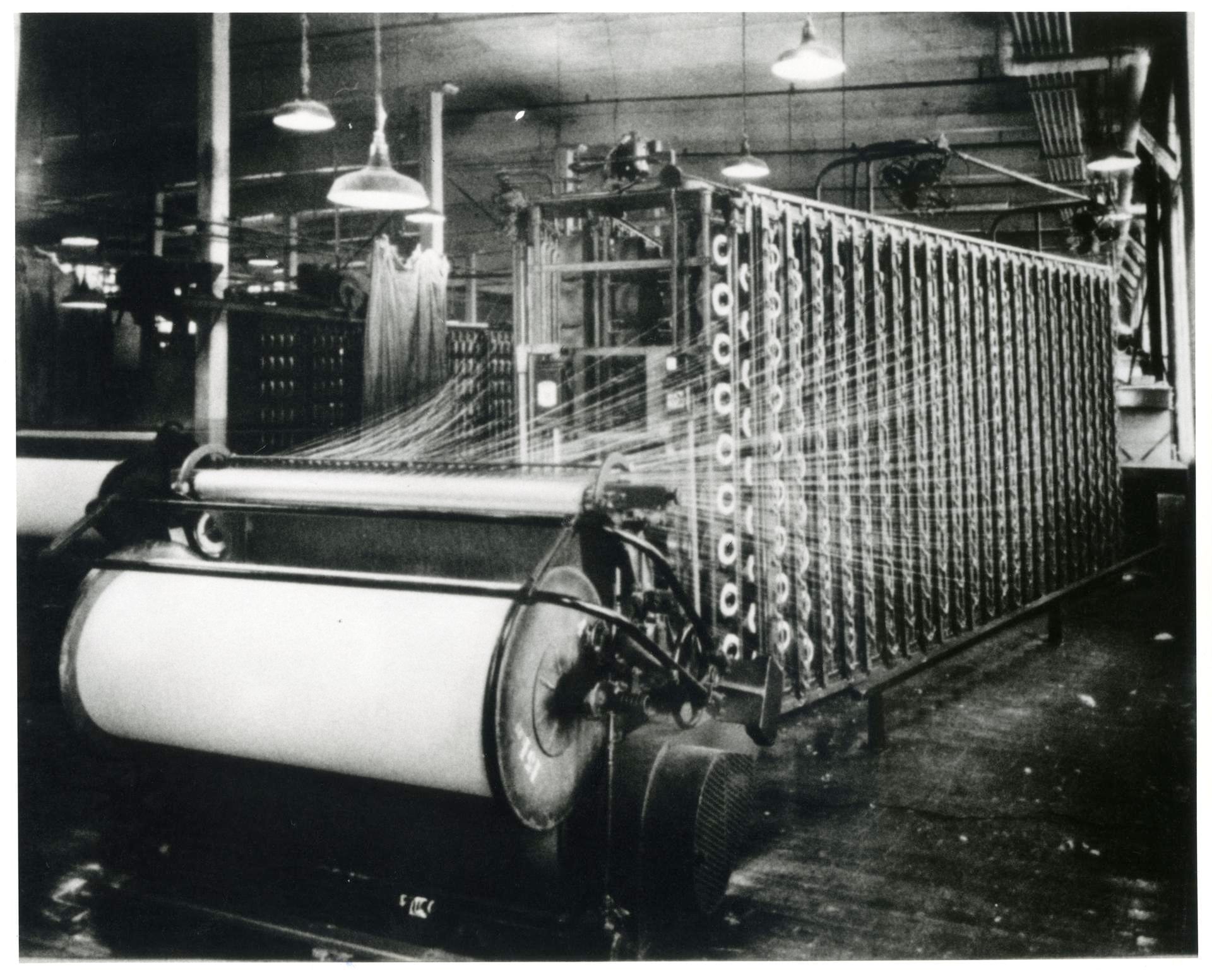

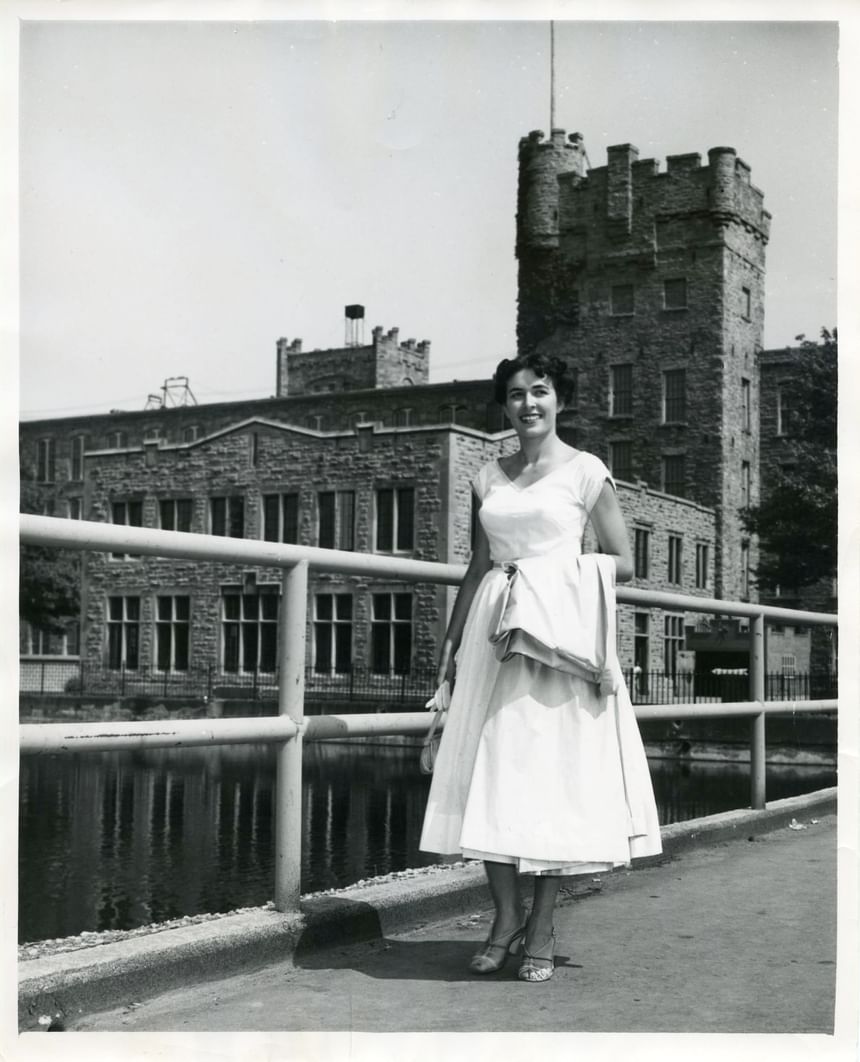

The architects designed buildings of monumental proportions, somewhat resembling a medieval castle with crenellated towers and bridges to the mills. The first part of the factory was completed in March 1877, and the last, in 1898. State-of-the-art equipment was imported from Great Britain and the Montreal Cotton Co. produced its first piece of fabric in May of that year.

The spinning mills were given nicknames over time. The “Old Montreal Mill” became “La Vieille” because it was the oldest structure. The southernmost building was called “South Mill”, and the “Louise” building was named after Queen Victoria’s daughter. “Empire” was homage to England and, finally, the last facility to be built was named “Gault”, after one of the founders and company president, Andrew F. Gault.

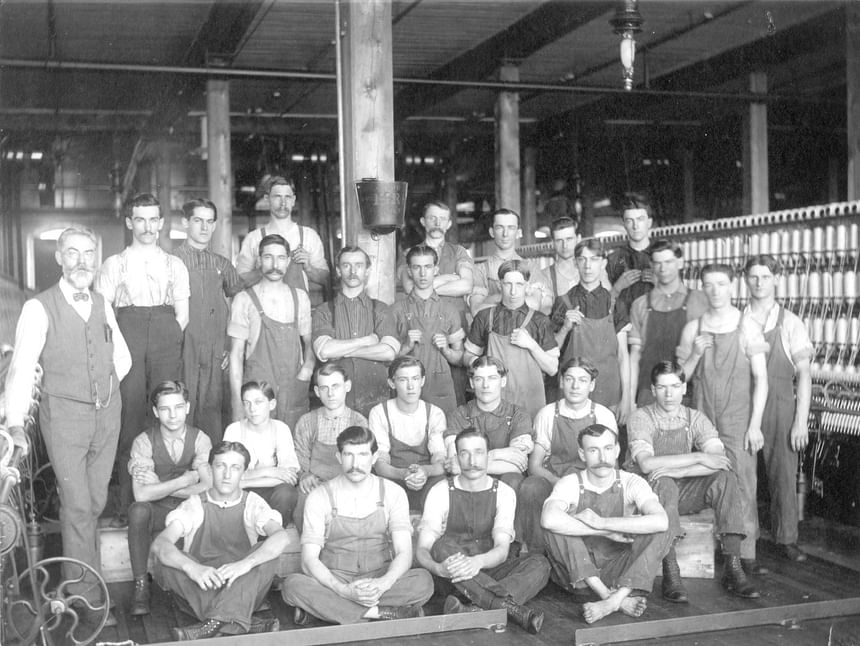

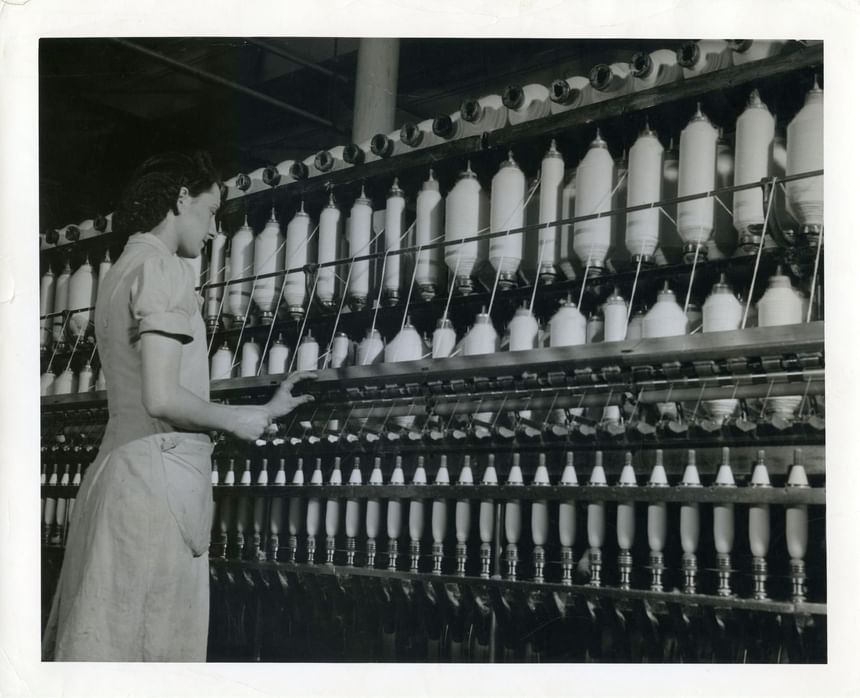

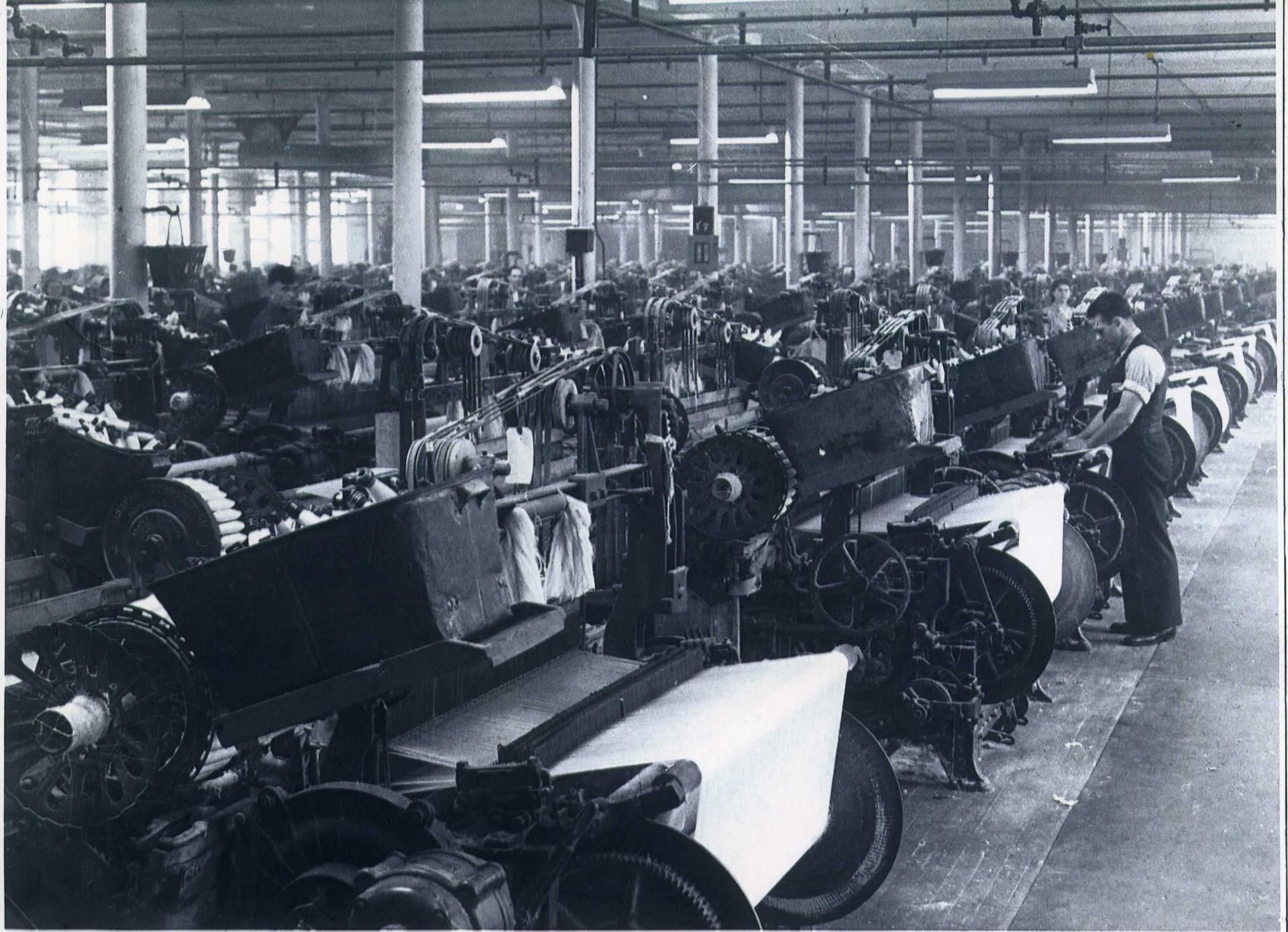

Most immigrants employed at the Montreal Cotton Co. came from England, Scotland, and Ireland. Many techniques and machines had been developed there, along with trade schools. Therefore, the company recruited English-speaking workers from the British Isles because they had the experience and qualifications needed for sound management and operation of the factory’s machines. For their part, French-Canadians made up a strong labour force. Noteworthy is the fact that the sponsors were partial to their countrymen, giving them management positions and the best-paying jobs.

While all or nearly all management staff was made up of unilingual English speakers, not all English-speaking employees were management. Some of them worked as spinners, weavers, or mechanics. However, for the most part, they did not associate with the local French population, which created friction and sporadic hostility in the younger generation. But generally both sides minded their own business.

At work, English dominated as the working language, and English vocabulary was francized; for example, strapping machine became strappeuse, and weaved or spun became wivé. Other words were abridged, such as factory ("factri"), Empire ("empy"), and Dominion Textile ("Dompi").

In these early days of industrialisation, spinning mills determined wages and working hours. For many years children worked alongside their parents and employees learned their jobs pretty much by hit and miss. Generally, employees spent 8-12 hours per day together. At one time, 50% of Salaberry-de-Valleyfield’s population worked for the Montreal Cotton Co.

Early in its tenure, the Montreal Cotton Co. invested in the town’s cultural infrastructures with organized leisure activities, and provided various public services. Urban development was marked by the creation of a complete neighbourhood of rental houses for their employees. The quarter had two very interesting features: it was probably the province’s first company town, and its architecture and layout were entirely new to Quebec at the time.

The employer wanted his workers to have proper housing and their children to get some level of schooling. Among others, a school and churches were built. Although its official name was Bellerive, this part of Salaberry-de-Valleyfield was known as the English Quarter, as nearly all the English-speaking employees of the company lived there. The company’s cultural infrastructures, such as the Moco Club, were mostly frequented by the English. The French-Canadian labourers did not have the time or the means to buy memberships.

Content sourced from The MUSO